By Ryan Boudwin, delivered at the NFB Utah convention on April 12, 2019.

Hi. My name is Ryan Boudwin. I am thirty-four years old, and I am blind. But I haven’t been blind very long.

February 2nd 2018 began a normal day, like any other. I was living a very comfortable life as a successful IT professional. I had been happily married for 11 years to my wife Annika and was the proud father of three boys. I was heavily involved in Scouting and in local politics. I had the day off to deal with a couple of medical appointments. I headed off to see my optometrist, expecting a routine vision exam and maybe a new pair of glasses. During my examination I failed a routine peripheral vision test. As soon as this happened I knew what was coming because of my family history, but it didn’t become real until my retinal scan came back positive for retinitis pigmentosa. Suddenly what had happened the previous night made sense; I had had a very close call in my car and had nearly hit a pedestrian that was wearing a reflective vest and a headlamp. At the time I had been thinking how on earth did I not see that guy? Well, now I knew.

I am the fourth of five children in my family to be diagnosed with RP, so when the news came I had a very good idea of what was coming and what the progression would be like. At this point I had donut shaped blind spots in both eyes and was not yet legally blind. My mid-periphery and nasal fields were gone, but my central vision and far periphery were still working. I likely could have hid my condition for some time, but I knew I needed to make some serious lifestyle changes. I’ve known a lot of people who insisted on continuing to drive long past their ability to do so safely, and I was determined to not be one of those people. I was a former police officer, and I had seen enough accidents to know that I was not willing to take the risk of continuing to drive. I did not want my desire for convenience to cost someone’s life.

Having been dealt a terrible hand of cards, I decided to try to think like an engineer and find the most optimal outcome possible for me. I wanted to be prepared for the future so that I wouldn’t have to be afraid of it. There is no treatment for my condition, and I knew my vision would get worse over time. It was inevitable. I wanted to develop the non-visual skills that I would need before I was entirely helpless without them, and adjust my lifestyle so my pending blindness could be mitigated as much as possible.

Within a week of my diagnosis I had ordered a white cane. I called a vocational rehabilitation counselor and tried to find out what resources were available for someone in my situation. I arranged for a field lesson with a cane instructor to get me started, and I went to my first meeting with the National Federation of the Blind. That first meeting I met a lot of people who had been through the same challenges I was facing now. I realized I was not alone in this struggle. But most importantly, I saw blind people who were clearly happy, well adjusted, and living the lives they wanted. And I knew I wanted to be like them. I didn’t want to let my blindness control my life.

I took a tour at the Training and Adjustment School. I knew immediately that this program was something I was going to need, but I didn’t know how I was going to be able to make it happen. At this time I was the sole breadwinner for my family. I was in a critical role at work, managing a team of engineers worldwide supporting the most critical accounts for our entire company. I had two choices before me. I could just try to keep working as if nothing had changed, until my vision got so bad that I would be unable to meet the needs of my employer and be out of a job, or I could try to find some way to take six months off, get the training I would need to be able to continue to work despite my blindness.

I worked with my employer to arrange for me to be able to take a leave of absence for six months so that I could attend the Training and Adjustment School full time. I had to give up my position with the team I was on, there was no way they could leave that vacant for six months, but I was promised I would still have a job in a similar role when I got back, managing a different team. I would live off of my disability insurance during my time away from work.

I also knew that where we were living was going to be a problem. We had a beautiful home in Saratoga Springs. We loved our neighborhood, we loved our neighbors, and we had finally made a lot of friends after three and a half years. Unfortunately for me, the public transportation there was almost non-existent, and I knew my decision to stop driving was going to mean pretty severe isolation if we stayed there. I knew I needed to move somewhere with better public transportation infrastructure if I was going to be able to maintain my independence and my sanity. Luckily for me, my wife was very understanding of the situation and together we decided to move. In less than a month after my diagnosis we had moved out and put the house on the market. We found a lot in Daybreak, a neighborhood in South Jordan, right next to a TRAX station and started building a new home. We lived with my wife’s parents while the house was under construction. I know that was a really hard thing for my family. And I know my wife gave up a lot when we left this place, she had so many friends, but she has always had my back through all of these challenges, and I will always be grateful for that.

While I was working out my leave of absence with HR, I still had to keep doing my job, which meant a business trip to our support office in Dublin, which would be my first time traveling with a cane in my hand. I had learned enough cane skills by then to use it as a low vision aid and avoid hazards, but I couldn’t yet navigate non-visually. At this point I figured I would use my cane outside, but that inside the office I would be fine without it- after all it was indoors, there’s no steps or surprises, right?

The first day I was there I was savagely attacked by a wild coat rack. My pride was injured a lot worse than my face, though. And so I started using my cane in the office too. I tried to enjoy my trip and I spent my evenings hanging out with my Irish engineers. I knew my night vision was compromised but I figured my cane would keep me safe. After a fun evening at a restaurant, I was walking back to the flat I had rented for the week. I took a wrong turn, and got myself thoroughly lost in a coastal neighborhood with no lighting. I ended up near a cliff by the sea; my cane gave me a heads up that there was a steep dropoff that could have gotten me seriously injured, and I was able to ultimately get home without further incident. But that made me very grateful for that first cane lesson I had gotten from Jerry Nealey.

By April I was a student at the Training and Adjustment school. A lot of people thought I was crazy for going so soon after my diagnosis. After all, I could still “see” to some extent and so I didn’t “need” the training yet. I was still “illegally blind,” after all. And I ended up having some surprises. After everything had been approved in writing by my employer, my disability insurance company rejected my claim and suddenly the money we had been planning on living on was gone. They said that because I wasn’t legally blind yet that I wasn’t truly disabled and thus ineligible for benefits. I spent every free minute I had on the phone with the insurance company trying to appeal my case, reminding them that if I waited until I was blind to learn these skills I wouldn’t have a job left to save. I thought I was going to have to drop out from the program and go back to work without learning what I had needed.

Well, my wife, Annika wasn’t having any of that. She knew that I needed to learn non-visual skills to be able to work long term and be a happy, engaged husband and father. She had been a full-time mother since our oldest child was born, but instead of letting me give up, she went and found a job so we could survive while I was out of work. She is now a TRAX operator at UTA. Many of you have probably ridden her train by now. Her support and determination helped keep me in the training program and made it possible for me to graduate.

Gratefully, I did eventually win my appeal with my insurance company. But I never would have been able to get through those challenges without the unconditional love and support of my devoted wife.

During this time, I started to get to know Dr. Kenneth Jernigan through the pages of Kenneth Jernigan: The Man, The Mission, The Movement. I grew to love his example, as a boy and then a man, faced with daunting challenges and without the support that I had. The more I learned of the NFB philosophy and the more discussions I had with my brothers and sisters in the Federation, the more determined I was that I would continue to live a fulfilling and satisfying life. Blindness was not going to hold me back.

Putting on my sleep shades and turning off the visual world for six months was one of the most difficult things I ever had to do. But I am so glad I did. Because I took action early, I was able to take a leave of absence and learn these skills while I still had a job worth saving. I was working in IT management when I was diagnosed. The training I have received is already making a massive difference as far as me being able to keep my job. In my present state I am able to work visually on a computer for part of every workday, but I am very sensitive to eye strain now and I can only get about two or three hours of productive work done that way. When I feel my eyes starting to go, I just close my eyes and keep on working with a screen reader so I am still able to put in a full workday, using the computer and braille skills I learned at the Training and Adjustment School. Because of the training I have received, I am able to still be the primary breadwinner for my family.

I don’t have to give up on my hobbies; my woodshop and home management classes have given me the confidence that I can problem solve issues for myself and that almost everything has a non-visual technique that can be used, even if I haven’t figured it out yet. I have always enjoyed woodworking and Ray’s class has made it clear that I can still enjoy it for the rest of my life. Learning braille means that I will always be able to enjoy great literature. I’ve even found non-visual techniques that make it so that I can still play pen and paper roleplaying games with my friends.

Now that my training is done, I use what vision I have as much as I can, using whatever blend of visual and non-visual skills makes sense for the task at hand. During the day my cane is primarily a low vision aid rather than my only means of navigation. It makes it so that I can look where I am going instead of staring at my feet; it makes it so that I don’t run into people anymore, and those around me have some clue that I might not see them. I always chop vegetables non-visually, using the skills I learned in my home management class, because my depth perception is so severely compromised. I watch movies with audio description so that I can take visual breaks and close my eyes whenever I feel the need to do so and still follow the story. I still watch baseball games with my kids, but now I use the radio audio feed so we can all still follow the game even when my eyes have decided that they are done working for the day.

One of the symptoms of RP is loss of night vision. In my case that means that every day I jump between the sighted world and the blind world with the setting of the sun. Because of the cane travel instruction I received at the Training and Adjustment School, I don’t fear the darkness.

My father died twenty years ago. And I still miss him every day. One of my fondest memories with him was going out to A&W after general conference. I have always tried to continue that tradition with friends or family as my circumstance permits as a way to feel connected with my father’s memory, but now I don’t drive. I decided to take my sons out with me anyway. We walked in the dark almost two miles to the restaurant, and I made new memories with my sons. My remaining vision is almost worthless in the dark, but I didn’t even hesitate that night. I just grabbed my cane and herded my three boys down Traverse Mountain. It was worth the trip. I am very grateful to Jennifer Kennedy and the other instructors at the school for giving me those skills.

As I was nearing the end of my time at the school, I had an appointment at the Moran Eye Center, and got an updated field test. The news was exactly what I knew to expect; that my RP was progressing; that my field loss was worse. After all the drugs they had put in my eyes and tests they had done that day, I stepped outside, unable to see much of anything. Without my training, I would have been helpless and would have had to just call someone to pick me up. Instead, I thought to myself, “Well, I can do this blindfolded.” And I got on the train and went and got myself some lunch instead of despairing about the future. As I ate I thought about how grateful I was that I was already learning the skills I needed to maintain my independence. It made the bitter cup of my impending blindness a lot easier to take.

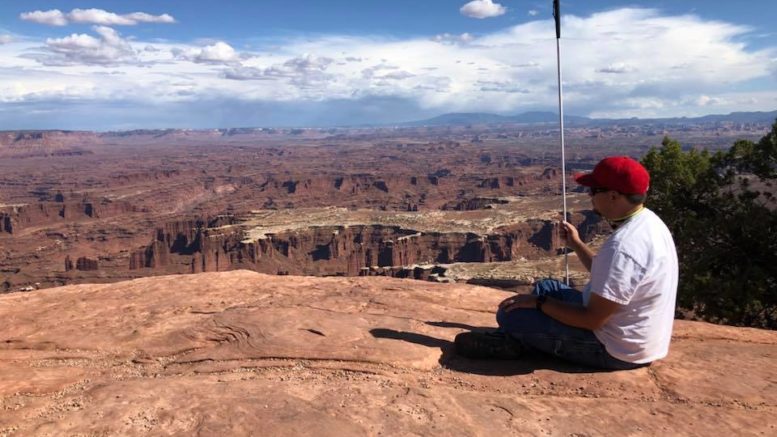

Some of the best parts of the Training and Adjustment School were the outdoor activities that we did under shades. We did a high ropes course; we went water skiing. We even went camping. Setting up a tent non-visually was more challenging than I thought it would be, but we did it. We went to Arches National Park and hiked and climbed among the rock arches there. We got on the Colorado river and went white water rafting. I even built a fire that I could not see.

Some people might think that taking blind people camping as part of a rehabilitation program is a waste of time and precious resources. But that camping experience made a massive difference in my life, because it gave me confidence that I will always be able to enjoy the outdoors. I am a proud Eagle Scout and a lifelong Scouter. I had thought that I would have to give up being a scout leader because of my blindness. After this camping experience, I knew that I could always contribute to Scouting. And I am currently serving as an assistant scoutmaster. Last fall I was inducted into the national honor society of Scouting, the Order of the Arrow. Joining this society requires going through an intense camping experience with very little food or equipment, a lot of manual labor, and a lot of hiking in the mountains in the dark, with a vow of silence until the very end. The process is called an “ordeal,” and I can tell you it is indeed quite the ordeal. But I did mine with a cane in my hand.

One of the biggest challenges for me from my condition are the psuedo-hallucinations I experience on a daily basis. I suffer from something known as Charles Bonnett syndrome. It happens to some people as they lose their vision, not everybody. In my case, I still perceive a full field of vision, but the parts of my eye that don’t work get filled in by my brain with whatever it decides ought to be there. Most of the time, it’s believable, but sometimes it gets very strange. I remember one day I was at church and was standing in the hallway. I saw a woman pacing, holding a black chihuahua in her arms. I started thinking, “What on earth did you bring that dog here for?” Then she took a few more steps and slipped into the part of my visual field that actually still works, and the dog turned into a baby. Suddenly I was really glad that I had chosen not to say anything about it. I’ve learned to have a sense of humor about it; sometimes when I have a really odd psuedo-hallucination then it becomes a challenge for my more artistically gifted relatives to try to draw what I see.

In October of last year I returned to work. On my return, I was having difficulty working out a schedule that would work for me and my family and the new team that I would be working with. Because of what I had learned as a member of the National Federation of the Blind, I was an effective advocate for myself, and I stood my ground when things got difficult. The Federation proved to be an important support for me in this difficult time, and I was able to get the advice and guidance that I needed for my situation.

Ultimately I found out my company needed a new recruiter that better understood the needs of our business. Having been one of their hiring managers, I knew what to look for, and I was particularly well prepared to find top engineering talent. I was selected for the role on a trial basis, because some of our management team were very skeptical that I would be able to keep up as a blind person. I was happy to prove them wrong. I exceeded all expectations and was given a permanent position as a technical recruiter. I now have a better job, with better working conditions, better work/life balance, and a bigger paycheck than I had before my diagnosis.

On December 5, 2018 I was finally declared legally blind. My disease has progressed enough that I only have twelve degrees left of reliable central vision. And with each eye exam I learn how much more vision I have lost. And I still mourn that loss. Training and philosophy have not made me immune to that pain. But what it has done is it has taken away the fear of blindness. I am not afraid. I know I can still be a great dad, a provider for my family and an engaged member of my community. And I can continue doing the things that matter to me. I am so grateful to everyone who has helped me along the way. This was one of the hardest things I have ever had to do, but now being blind is just an inconvenience instead of a crippling disability. I still have a life to live. And I am truly living the life I want.

Be the first to comment on "Why I am a Federationist"